Monday, September 20, 2010

A Day At ETS-Lindgren: A Company You Know, But Not By Name (Yet)

Posted by Jon Westfall in "Android Articles, Resources & Developer" @ 08:00 AM

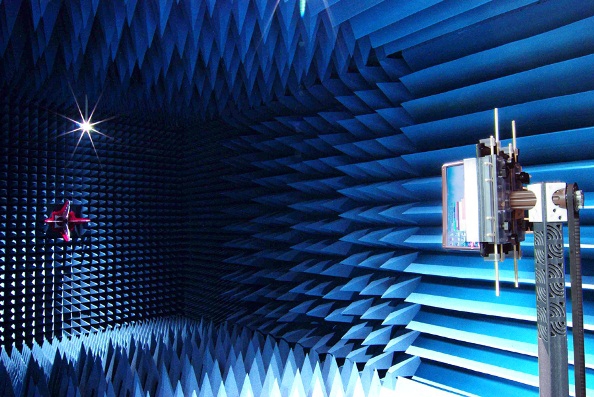

On a warm and muggy Austin morning, I arrived at a fairly nondescript building nestled inside an office park along a road that had recently suffered a bit of flood damage from tropical storm Hermine. The location that I was visiting was the headquarters of ETS-Lindgren, which in their own words is "... a specialty manufacturing and construction company which builds facilities and the component hardware and software required to make world class measurements under carefully controlled electrical... conditions". What does that mean? It means they do some pretty cool things that help make the gadgets we all love to use the best they can be. Our group consisted of myself, Steven Hughes (BHighlyMobile & Boston Pocket PC), Judie Lipsett Stanford (Gear Diary), Daniel Lim (SlashGear), Andru Edwards (Gear Live), and Brad Sams (Neowin). We'd all received information about ETS-Lindgren prior to our visit, however I don't think any of us expected to see half of what we did during our six hour tour and discussion. ETS-Lindgren is one of those companies that flies way below the radar when it comes to publicity and name recognition. However, most of us have seen their work. For example, most of the time when you see pictures online, or in movies or TV, of a room that looks like this...

Figure 1: An anechoic chamber.

...You've likely seen their work. They build these test anechoic chambers (and the components that go inside of them) so that very precise measurements of energy may be taken. To take those measurements you must first eliminate all sources from the outside world, thus the pyramid shaped foam pieces, extremely thick walls, and electromagnetically shielded housings for the lights and equipment. The level of detail is amazing, and the rooms are quite impressive, but not as impressive as the measurements that are done.

Figure 2: Testing facilities with three chambers.

The shot above is the area of their facility that we spent the most time in. The tests they ran for us were conducted in a chamber just behind this raised platform. Upon arriving at their headquarters, we listened to a few presentations about the company and after about an hour were taken to the testing area. It's quite interesting to go from a cubicle farm to a lab in 10 seconds flat; imagine our surprise when we saw the back of the building featured a huge factory where they manufacturer most of the components that go into the test chambers! We were shown some pretty cool stuff before the first of several tests were run for us, including this guy:

Figure 3: A phantom head!

Yep folks, that's what they refer to as a Phantom Head. He's hollow, so he can be filled with liquid to approximate the chemical makeup of the human head. The phantom allows you to use hands, if you'd like, to hold the device up to the head, but surprisingly CTIA requirements that providers use to measure signal strength only require the "head" test - hands are not yet required. But they have hands - a lot of them, in all different configurations for each style of phone (flip, bar, PDA). Each hand is molded after researchers observed a number of humans using such a style phone in the lab, so as to get the average sized hand in the most common position, to try to make the test as applicable to as many humans as possible.

Figure 4: A box of hands, with calibration/measuring devices.

The testing that we were shown is what's called "Over the Air" Performance Testing (OTA). ETS-Lindgren had the first lab authorized by CTIA, and builds greater than 80% of all CTIA certified labs. OTA Testing is much more complex than asking "Can you hear me now" to your buddy at the other end! Including being less qualitative (e.g., subjective) and more precise, it also allows providers to better estimate their "link budget", or the amount of performance they find acceptable on their networks. How does OTA Do this? Well here's the quick and dirty version.

The strength of a link between two radio devices is a function of the power emitted by one device and the sensitivity of the antenna of the other device. To figure out this, one needs to know these variables in a controlled area - like the chambers shown above. Once the numbers are crunched, one gets a rating in decibels (referenced to 1 miliwatt; dB or dBm). The decibel rating is on a log scale, such that a loss of 3 dB is equivalent to the loss of 50% of the signal strength. Take another 3 dB away, and you're at 25% of the original signal, and so on. Of course the measurements that ETS-Lindgren takes in the lab are under optimal transmission and receive circumstances, its up to providers themselves to figure out what's reasonable in the field. Dense cities with lots of objects to impede signals will do just that; large flat land with very few large buildings or structures will necessarily provide better reception.

In addition to the OTA testing, we also learned about a buzzword I had heard but had no idea what it actually meant: MIMO. MIMO stands for Multiple-Input Multiple-Output technology, and again without going into too much detail, it means that a device can have multiple antennas transmitting and receiving simultaneously over one link. The technology is able to determine mathematically which antenna a channel is meant for and filter out the signal when processing that channel. Think of the difference as serial processing to parallel, although with less channels (at this time) than your parallel port allows.